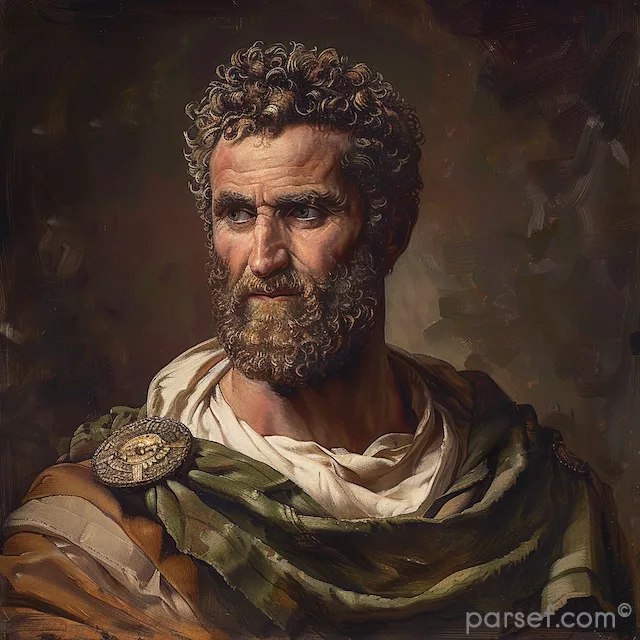

Roman Emperor Elagabalus (218-222 CE)

Elagabalus: The Boy Emperor Who Shocked Rome

Elagabalus, born as Varius Avitus Bassianus in 203 CE, is one of the most controversial and enigmatic figures in Roman history. His reign, which lasted from 218 to 222 CE, was marked by scandal, religious upheaval, and eccentric behavior that shocked the conservative Roman establishment. Ascending the throne at the age of just 14, Elagabalus attempted to impose his personal religious beliefs on the Roman Empire and engaged in behavior that challenged the traditional norms of Roman society. His reign was short-lived, and his downfall was as dramatic as his rise to power. Despite the sensational accounts of his reign, often colored by bias and exaggeration, Elagabalus remains a fascinating figure who represents the challenges of maintaining power in the Roman Empire.

Early Life and Background

Elagabalus was born in Emesa, a city in the Roman province of Syria (modern-day Homs, Syria), to a prominent family with strong ties to the Severan dynasty. His mother, Julia Soaemias, and grandmother, Julia Maesa, were influential members of the Severan family, being related to the Empress Julia Domna, the wife of Emperor Septimius Severus and mother of Emperor Caracalla. Elagabalus's father, Sextus Varius Marcellus, was a Roman senator of equestrian rank, but it was through his mother’s side that Elagabalus would eventually claim the imperial throne.

The young Elagabalus was raised in Emesa, where his family served as hereditary priests of the sun god Elagabal, the chief deity of the region. From an early age, Elagabalus was deeply immersed in the religious traditions of his homeland, and he served as the high priest of Elagabal, a role that would later become central to his identity as emperor.

When Emperor Caracalla was assassinated in 217 CE, the Roman Empire was thrown into turmoil. Macrinus, a former Praetorian Prefect, seized power, becoming the first emperor of the equestrian order. However, his reign was unpopular, particularly with the Severan loyalists and the eastern provinces. Sensing an opportunity, Julia Maesa, who had been exiled to Syria after Caracalla’s death, began to plot her family's return to power. She capitalized on the widespread discontent with Macrinus and promoted her grandson, Elagabalus, as the legitimate heir to the Severan dynasty, falsely claiming that he was the illegitimate son of Caracalla.

The Rise to Power

Julia Maesa’s political acumen and the Severan family’s wealth and influence were crucial in Elagabalus’s rise to power. In 218 CE, Maesa managed to win the loyalty of the Roman legions stationed in Syria by promising them substantial financial rewards and by emphasizing Elagabalus's alleged connection to Caracalla. The legions proclaimed the young priest emperor, and civil war soon erupted between the forces of Macrinus and those loyal to Elagabalus.

The conflict culminated in the Battle of Antioch in June 218 CE, where Macrinus’s forces were decisively defeated. Macrinus attempted to flee but was captured and executed. Elagabalus, now firmly in control, made his triumphant entry into Rome as the new emperor, marking the return of the Severan dynasty to power.

Elagabalus’s ascension to the throne at such a young age was unprecedented, and his reign was initially guided by his grandmother, Julia Maesa, and his mother, Julia Soaemias, both of whom wielded significant influence in the imperial court. However, it quickly became clear that Elagabalus had his own ideas about how he would rule, and these ideas would soon bring him into conflict with the Roman establishment.

Religious Reforms and Controversies

One of the most defining aspects of Elagabalus’s reign was his fervent devotion to the god Elagabal, whom he sought to elevate above all other deities in the Roman pantheon. Upon arriving in Rome, Elagabalus brought with him the sacred black stone of Emesa, which was believed to be the earthly manifestation of Elagabal. He had this stone installed in a grand new temple, the Elagabalium, on the Palatine Hill, where he personally presided over the religious ceremonies.

Elagabalus’s attempts to impose his eastern religious practices on the traditionally conservative and polytheistic Roman society were met with strong resistance. The emperor declared Elagabal to be the supreme god, superior even to Jupiter, the chief deity of the Roman pantheon. He ordered the merging of Roman religious festivals with those dedicated to Elagabal and insisted that his god be worshiped by all Romans. This religious revolution, which effectively attempted to replace the traditional Roman religion with the worship of a foreign deity, was seen as sacrilege by many.

Elagabalus’s religious zeal extended to his personal life, where he often blended religious rituals with his daily activities. He shocked the Roman populace by participating in elaborate and unconventional ceremonies, some of which included the sacrifice of children from noble families, although these accounts may be exaggerated by later historians hostile to his rule. His behavior was perceived as a direct challenge to the religious and social norms of Rome, further alienating the Senate, the military, and the Roman people.

Personal Eccentricities and Scandals

In addition to his religious reforms, Elagabalus’s personal life was a source of constant scandal and controversy. He was known for his extravagant and decadent lifestyle, which was often at odds with the austere traditions of the Roman aristocracy. The young emperor indulged in lavish banquets, wearing extravagant clothing, and adorning himself with jewelry and makeup, behaviors that were seen as effeminate and unbecoming of a Roman ruler.

Elagabalus’s sexual behavior was also a major source of scandal. He is reported to have had a series of relationships with both men and women, including marrying multiple times during his reign. His most infamous relationship was with a charioteer named Hierocles, whom he reportedly referred to as his husband. Ancient sources claim that Elagabalus sought to have himself declared legally female so that he could marry Hierocles, although this account is likely embellished by later historians.

These behaviors, combined with his religious practices, created an image of Elagabalus as a ruler who was not only out of touch with Roman values but also actively subverting them. The emperor’s actions alienated the Senate, the military, and the broader population, leading to widespread discontent with his rule.

Political Instability and the Role of Julia Maesa

Throughout Elagabalus’s reign, the real power behind the throne often appeared to be his grandmother, Julia Maesa. A shrewd and experienced political operator, Maesa recognized the growing discontent with Elagabalus’s rule and took steps to secure her family’s hold on power. She began to distance herself from her grandson’s more extreme behaviors and turned her attention to another potential successor: her other grandson, Severus Alexander.

Severus Alexander, the son of Julia Maesa’s younger daughter Julia Mamaea, was everything Elagabalus was not—modest, respectful of Roman traditions, and widely regarded as a more suitable candidate for the throne. Recognizing the threat posed by his cousin, Elagabalus initially attempted to marginalize Severus Alexander, but Julia Maesa skillfully manipulated the situation to ensure her younger grandson’s survival.

In 221 CE, under pressure from his grandmother and the Praetorian Guard, Elagabalus was forced to adopt Severus Alexander as his heir. This decision was intended to appease the growing opposition to his rule, but it ultimately sealed his fate. The Praetorian Guard, who had become increasingly disillusioned with Elagabalus, began to transfer their loyalty to Severus Alexander, viewing him as a more stable and traditional ruler.

Downfall and Assassination

By 222 CE, the situation had reached a breaking point. Elagabalus, realizing that he was losing control, attempted to undermine Severus Alexander by spreading rumors of his cousin’s death. This move backfired spectacularly, as the Praetorian Guard, angered by the emperor’s actions, turned against him.

On March 11, 222 CE, the Praetorian Guard stormed the imperial palace, intent on removing Elagabalus from power. The emperor and his mother, Julia Soaemias, attempted to flee, but they were quickly captured. Both were brutally murdered by the guards, their bodies dragged through the streets of Rome before being thrown into the Tiber River, a fate reserved for the most despised enemies of the state.

With Elagabalus’s death, Severus Alexander was proclaimed emperor, and the Severan dynasty was restored to power under more conventional and stable leadership. The Senate, eager to distance itself from the controversial reign of Elagabalus, ordered a damnatio memoriae against him, seeking to erase his name and memory from the public record. Statues of Elagabalus were destroyed, and inscriptions bearing his name were removed or altered. Despite these efforts, however, Elagabalus’s reign remained a subject of fascination and horror in the centuries that followed.

Legacy

The legacy of Elagabalus is one of the most debated and sensationalized in Roman history. Much of what we know about his reign comes from sources like the Historia Augusta and the works of Cassius Dio, both of which were written by historians who were deeply critical of his rule. These accounts, while invaluable for understanding the period, are also filled with bias and exaggeration, making it difficult to separate fact from fiction.

Elagabalus is often portrayed as a symbol of the excesses and decadence that contributed to the decline of the Roman Empire. His attempts to impose his religious beliefs, his unconventional personal life, and his disregard for Roman traditions made him a figure of both intrigue and revulsion. Yet, his reign also highlights the challenges faced by a young and inexperienced ruler in an empire where power was increasingly dependent on the support of the military and the aristocracy.

In the broader context of Roman history, Elagabalus represents a period of instability and transition, where the traditional structures of power were being tested by new forces and ideas. His reign, though brief, left an indelible mark on the Roman Empire, serving as a cautionary tale about the dangers of absolute power and the complexities of leadership in a vast and diverse empire.

Elagabalus is one of the most infamous Roman emperors, known for his extravagant and unconventional lifestyle. Initially a high priest of the Syrian sun god Elagabal, he ascended to the imperial throne at a young age. His reign was marked by a series of shocking acts, including introducing the worship of his namesake deity to Rome, a move that deeply offended the Roman populace. Elagabalus is often portrayed as effeminate and decadent, indulging in lavish feasts, extravagant clothing, and unconventional sexual practices. These behaviors, combined with his erratic decision-making, alienated both the Senate and the army.

Despite his short reign, Elagabalus' impact on Roman society was significant. His attempts to reform Roman religion and his disregard for traditional values caused widespread outrage. Ultimately, his rule became untenable, and he was assassinated by the Praetorian Guard, bringing a swift end to his tumultuous reign. His memory was subsequently erased from official records, contributing to the legendary status he holds in history.

Latest

Popular

Useful